Question

We've been having a terrible problem getting people to follow the drawing or remember to do things in the proper order. It doesn't seem to matter if the worker has a lot of experience or is a complete greenhorn. They still space out. This happens with $15/hr guys and $25/hr guys.

It has been suggested that we print up a list of steps for each thing we make and have that list follow the work order throughout the shop. The recommendation was that the worker initial each task on the list as they complete the task.

One local shop that has implemented this said that it seemed to add some accountability to the worker. It also communicated the fact that management is paying attention to what everybody works on. This business owner said that it seemed to work out for them and the re-work rate went down.

Has anybody else done anything like this? Making these lists seems awfully tedious but probably not as expensive as having to re-do things. Any thoughts about how to get people to pay more attention or do things in the right order?

Forum Responses

(Business and Management Forum)

From contributor S:

First some questions. What are your products? What machines? How many employees on the floor? What is your break down of operators to assemblers? Give us a brief description of your process.

I think writing down your process is not the solution, just the beginning to the solution. Most likely your process is not very stream lined and hard to follow in a linear way. In our shop it is not necessary to write it down the flow of production defines itself. I know that sounds philosophical but I mean it literally.

Contributor G - can you explain visual control? What do you mean?

The only way to use a list as tool for implementing change is in conjunction with cross-training your shop personnel. This standardizes production and has everyone reading off the same page and will increase accountability. Kind of hard to BS someone when everyone knows how to do it.

Keep in mind that you pay your guys their hourly rate for a reason. The $25/hr guy is supposed to have more experience and less production issues than the $15/hr guys. That said, if they are both making legitimate mistakes, you have a process-problem. The only way to correct this is to literally dissect the problem from start to the introduction of the mistake, find the cause, fix-it, get everyone reading off the same page, then rinse-and-repeat with any future issues. If you have to tell a $52K/year employee how to do something production related or how to avoid mistakes, they are overpaid in my opinion.

Approach it from a process-improvement point of view instead of finger-pointing to say “this is your fault" and show how it costs the company money, and the accountability becomes part of the new process.

There are plenty of process-improvement systems out there (TQM, Sigma-Six, LEAN, etc,), and they all follow the basic – plan, do, check, act model to a certain extent with their own flavor added, but most are designed for the drone mentality instead of the critical thinking mentality.

Think of it this way - do your kids need a check-list to do their chores once they've been doing them for a year or more? Or do they just need the right motivation?! So, if they can get along with going to school, homework, after school activities, part-time jobs (learning more things to do), and do their chores, all by themselves, what is the excuse for someone who is getting paid to do it as a profession?

We've implemented and used a lot of these systems over the years, and they are absolutely useful, but I want to warn you, you can also get lost in the minutiae and dogmatic use of them and you can end up doing the opposite of what you are trying to accomplish - especially if you are a small company. These systems do not work for every company the same way. Creating an environment where people take ownership in what they do is much more productive and customer focused than any process you can document or implement.

The clearly defined steps signal to everybody exactly what the current status of production is. If the project requires seven steps and you are currently on number four then one-three have been completed and five, six, and seven remain. This eliminates ambiguity which eliminates consternation and bad decisions.

Just as all activities have an optimum method and sequence they also occur at an optimum location within the building. This part is harder for the small shop but not insurmountable. If you want to ensure that only 1 1/4 inch screws are used for drawer box assembly then make sure drawer box assembly only happens where the 1 1/4 inch screws live. This is a concept called "Poke yoka" in Lean parlance. It means to idiot proof something.

Poke Yoka is linked to "Sustain", the 5th S of a 5S program (Sweep > Sort > Simplify > Sustain). Maybe what you need (and what this dialog is really all about) is how to "Sustain" best practices.

What do you guys think of having a list of numbered processes that follow each work order? This could be something that the worker checks off or initials as he/she completes each task. This would seem to add some accountability to the program and simple accountability might be a big part of the problem. If you signal to your crew that best practice is something that is going to be noticed or measured you will probably get more “best practice.”

Contributor K and P - what do you think of lists like this? I understand that Contributor K thinks this produces "drone" type behavior but are there ways this can be done without stifling too much creativity? Would this set of best practice processes benefit from more formality (actually writing it down) or would the world be a happier place if this was more democratically decided by those who actually do the tasks?

To contributor K: I don't see lean as creating drones in fact quite the opposite.

To the original questioner: Since you are not sharing any more information I'm going to assume that the basic problem is staring at you in the mirror. What you are trying to create by any tools is a productive culture, this is done on the shop floor with hands on. In lean they call this get your boots on (Gemba). You have to look to get a profound understanding of what is going on, in other words you have to define the problem or situation this is 90% of the battle and this is not done in the ivory tower like a bean counter would. One tool I would use that is some sort of metric. Metrics are not subjective they are scientific and tell you where to look. In my mind the culture is number one.

From that point on, I don't need a micro list breaking down how to make a drawer step-by-step, but the macro direction that a drawer needs to be made. Cross-training is a critical component. There will always be someone on the team who makes a drawer faster or someone who is better at finishing. But if you want to create a competent staff, you will cross-train them on all areas of production. Who wants to make only drawers their whole life no matter how fast you can do it?

There would be no such thing as jigs and other methods to produce items if all we did was follow lists instead of being accountable for what we produce. It tamps down the reason to ask - "why?" which leads to innovation.

So, if by "list" you mean I need (eight) drawers made, (14) face-frames, (14) cabinet boxes, along with the appropriate cutlists, etc.... I am with you... if by "list" you mean break down every process that has to be checked off as you go along, this is where I think it is anti-productive and creating a drone environment that relies more on step-by-step than critical thinking. Checklists should be production-related, not process-related. Process is where training comes in, production is where accountability comes in.

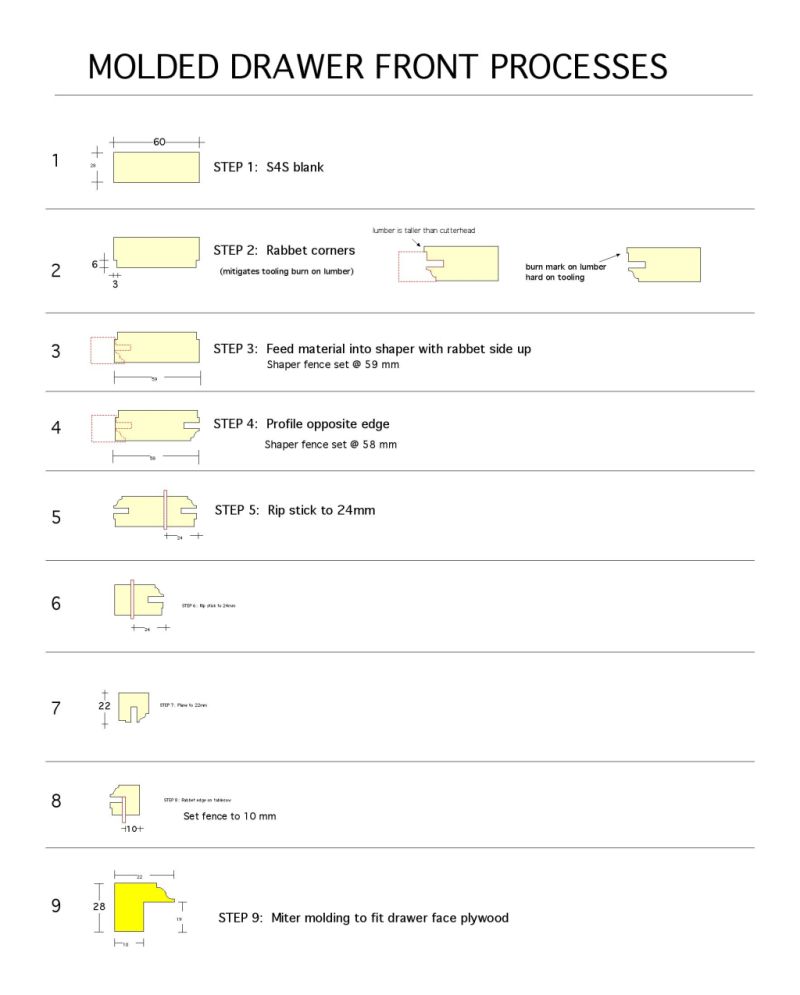

The first time this list was employed the mental horsepower was freed up to create a system for cutting these moldings to size and mitering them that did not depend on a tape rule or pencil mark. This list entirely changed the sequence and method we use for creating these molded faces. Without the list we would have been bogged down with history. It would have continued to be done "the way it has always been done". Now that we have chopping to size and mitering under control we can focus on how we clamp the parts. Thinking things through with a written list has generated a lot of opportunities for craftspeople to get better at what they do and apprentices to become craftsmen. It is the Simplify > Standardize part of the 5S program.

What I'm talking about is the culture. The idea behind lean is to empower the worker and get him engaged to contribute and create a bottom up culture. This is vastly more important than any tools an organization might use.

Basically, when one person's component of a job is complete, they look to their left and help that person. The standards manual serves two purposes. First, the person who is working outside of their "niche" has access to the information required to complete the task successfully. Secondly, it reinforces adherence to those standards - if the primary person starts arbitrarily changing the way things are done, the helper will know right away that they are being led down a rabbit hole. Now some may think that this makes us inflexible and are reinforcing the drone mentality of which Contributor K spoke.

The opposite is actually true. When someone is being assisted with a task they become the team leader. They are accountable for the successful completion of the task. Power tripping is held in abeyance by the fact that the person who is a team leader on Monday could very well be the helper on Wednesday - the do unto others thing seems to be working. As well, feeling responsible for a certain area of production within the company motivates people to try to innovate and improve the process - new ideas are submitted, tested, and then either implemented, rejected, or amalgamated with the old standard. The only part that was difficult in the implementation was getting people to read the bloody book in the first place. Oh, one thing I forgot to mention - in many of our processes the manual states not only what to do but why we do it that way - I think someone else already stated that a system isn't much use if the people who need to implement it don't buy in to it. As far as metrics go, in the last two months our remakes are down by roughly 50% and individual productivity is up about 20.

I am not against manuals, lists, process-improvement, etc. We use them also, but what we also believe in is cross-training, and it makes everyone accountable to each other. If they see something not right, they don't continue processing it, it is addressed. That could not happen however, if person A did not know how to produce what person B does. The part you need to realize is that with all process-improvement, you reach a point of diminishing returns - the excitement and newness wears off and an equilibrium sets in and you have a new normal. I am all-for improving the process nonetheless because it is a better normal than previous. All I am encouraging you to do is to be careful not to get caught up in the minutiae.

Something that is repeatable is quite easy to come up with a workable metric and very useful. On custom work that is mostly non-repeatable the unit of measure that is repeatable is elusive. I see where some guys say they can come within 5% on one-off monumental type work. I would love to know how they accomplish this. This is not a trivial subject as predicting how long a job is going to take is at the very heart of your survival, especially on large complicated jobs.

This works in sales also. Constraining your options to either this or that makes it easier to ask your customer which option they prefer. They can always tell you the answer to this question. It's when they have a universe of options that they can't decide at all. Let us imagine you want to train a new person how to build a drawer box: At our shop the sides get treated differently from the fronts and backs. The sides get sanded on three corners and grooved on one. The fronts and backs get sanded on one corner, grooved on one corner and pocket drilled. The drawer bottoms only get rabbeted. All three parts have a different labeling protocol. That is eleven separate things to learn.

What kind of sand paper should we use on the sanding block? Where does it live in the building? Who do we buy it from? What do they call it? Now you're up to fifteen events. This is all minutia. You can manage it in your head or you can write it down. The veterans may not need this much input but if somebody had of given it to them they'd have become competent quicker.

A great example of minutia is measuring travel time between operations. Who has resources for that level of analysis? It is interesting to note, however, that many if not most before and after Lean transformations measure outcome in reduced travel time. Reduced travel time reduces space required to produce product. In this respect reducing travel costs is a capacity generator. Reducing travel costs may also reduce time from order to ship. In this respect reducing travel time becomes a cash flow enhancer.

Focusing on minutia at this level just increased your capacity, lowered your overhead and improved your cashflow. What is not to like about that? Imagine if you added a CNC machining center to a culture that celebrated minutia. Always remember, just because you don't feel the need to corral minutia does not mean you aren't tripping over it.

One possible strategy is for your foreman to arrive early and wander around looking for clues. If he sees a pile of white parts he can surmise that at least some of the shelves got cut. He gathers these clues and arrives at conclusion and bases his strategy on that conclusion.

The weak spot to this approach is it takes a certain amount of time to wander around divining the information and sometimes the conclusions he arrives at are not accurate. He may think that all the shelves are cut when sometimes they are not. He may not discover this pile of parts or might misinterpret what they are and have someone else cut the shelves again. On more than one occasion I have had the foreman arrive early and cut up things that the afternoon crew already made. Somehow the status of every activity is made apparent to the stakeholders. This could involve a secret handshake. Sometimes it is just assumed that you would know what I know. Sometimes you consult a list and see what has been cross off of it. The activity of monitoring status does not go away because you eschew lists. You just monitor status in a different way.

My contention is that a list of processes crossed off with a yellow highlighter produces less ambiguous conclusions and ultimately costs less to accomplish. The reason I say that it costs less is the alternative has to also factor in the cost associated with making shelves twice (or not at all).

Have you ever had to send someone to a jobsite to measure shelves for a cabinet that was already in your building? If this is the case you have already spent the money. Another cost, albeit much harder to quantify, is the cost of failure. People don't like to make mistakes and they tend to be a little more tentative sometimes in order to keep the mistake from happening. A properly maintained list is going to provide the basis for more confidence and that will provide the basis for more speed. In the end it is still going to come down to a list. The list is either in your head or written down but it is still a list.

If a pizza man needs a check-list to know how to make a pizza after he's been trained on how to do so, I would say the training is sub-par or the person is not cut-out for the job. With cross-training everyone is accountable to each other. Just as if you were to pass your drawer off to the foreman to inspect before it moves on, it is the same when you pass it to someone who already knows what to expect. You are apt to do it right the first time. People who make repeat mistakes and don't learn from these mistakes and don't benefit from retraining are not going to benefit from a list.

You either understand that I need (eight) drawers at such and such size or you don't. This goes for any other part you were trained to make in our shop (experience or not). If you don't, we'll correct your understanding, but if after this, you continue to have problems fulfilling this task, we probably won't have a long-term relationship.

You are accountable to train to produce the product you need according to your standards, the person making the part is accountable for making sure it gets done correctly. Does that mean there will never be mistakes - of course not. I've transposed a number or two in my time after a hard day. But that doesn't mean that I then add another item to a checklist to make sure I double check the numbers, which is condescending in its reading, it means I be more careful next time. This is an example of where I believe you can get lost in the minutiae of these systems.

We are in the middle of condo project and have to build 60 stand-alone closets. They are like a giant wardrobe assembly. Because they are all the same and there is no assembly (they are wrapped and shipped) we changed or usual one assembly flow into a cut/band process; then a boring packing process. I was very proud when I saw the workers start moving the machines and parts rack around to make things flow better for this one day of work. Because they all work together in a highly integrated fashion they are acutely aware of the down-stream and up-stream process difficulties. So this makes them all work together to simplify the process, even to the point of relocating the grooving machine and several very heavy racks.